- Flip The Tortoise

- Posts

- Ostriches In Australia

Ostriches In Australia

Suck on that, Mr Kennedy!

When I was in grade four (or 4th grade for my American friends), I had to write an assignment about a country.

I chose Australia because my teacher, Mr Kennedy, was from Australia.

I thought that writing about Australia might endear him to my report (resulting in a better grade) more than writing about any other country.

I was dramatically wrong.

We had to present our project to the class.

I got to the part in my presentation where I talked about flora, fauna, and wildlife.

There’s so much interesting stuff for a kid to talk about when it comes to animals down under.

I still have this vivid memory of Mr Kennedy exclaiming loudly in the middle of my presentation, “There are no ostriches in Australia!”

The ostrich section in the report might have been a bit overwritten and unnecessarily expansive. Who knew there were ostriches in Australia? Koalas, crocodiles, snakes, and spiders were obviously in the outback. But ostriches? I was fascinated by the idea.

My family’s Funk and Wagnalls encyclopedias were clear: there were ostriches in Australia.

I had even included a photocopy of an Ostrich image from the encyclopedia in my report, presumably an Australian ostrich, with its head between its legs.

Funk and Wagnalls was my trusted source for most question-answering.

My encyclopedia set and TV Ontario were pretty much the only extra-educational materials I had access.

Mr Kennedy still adamantly disagreed.

No ostriches in Australia!

My grade on this assignment reflected his disagreement.

And who was I to argue?

I was just a kid who had only one primary reference source.

Did Funk and or Wagnalls get it wrong?

No.

Any ten-year-old with an iPhone could Google the question today and get a credible answer.

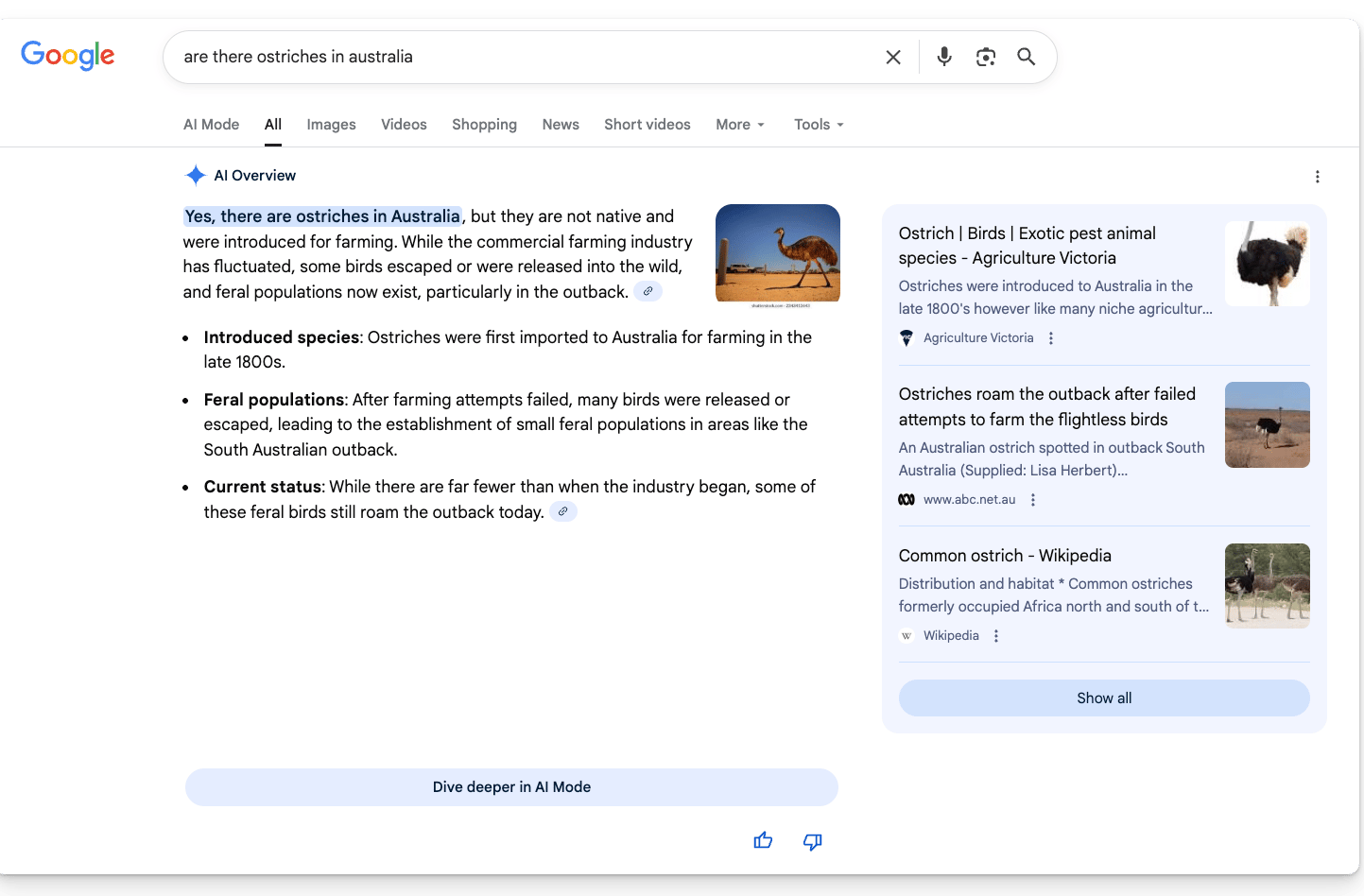

And Google will give you the answer in its AI Overview: “Yes, there are ostriches in Australia, but they are not native and were introduced for farming.”

Suck on that, Mr Kennedy!

My ostrich escapade resurfaced in my brain this morning when I read about Gabriel Petersson, a 23-year-old high school dropout who got hired at OpenAI.

This wunderkind taught himself everything he needed to know about his job at an AI company, a job usually reserved for folks who have PhDs in data science, using ChatGPT as a real-time tutor.

For all of his life, I’m willing to bet there were no Mr Kennedys in telling Gabriel he was wrong.

And if they did, he just Googled that shit.

He grew up in an era where most of the world’s knowledge was generally available and indexed for him to access.

He probably doesn’t know about Funk or Wagnalls.

Gabe can use tools like ChatGPT to train himself on skills he doesn’t have.

Students today, armed with all human knowledge at their fingertips, face a fundamental question about the value of post-secondary education.

"Universities no longer hold exclusive rights to foundational knowledge," Petersson stated in a recent podcast interview, emphasizing that AI tools allow anyone to acquire essential skills.

Why go to school if you can have AI teach you everything you need?

It is a vexing, existential threat to academia.

Our educational institutions aren’t equipped to address it.

In the interim, colleges and universities are laser-focused on the fear that students are using AI to cheat.

Spoiler alert: students were already cheating.

“A paper from Stanford researchers last year suggested that cheating overall hadn’t increased since the advent of AI. (Though it also suggested there wasn’t that much room for increase: Roughly two-thirds of high school students reported cheating in some way.)”

I was a university dropout.

(I prefer the phrase “I left university” rather than “dropped out,” since in my case, it was a choice.)

Also, I finished university 25 years later during COVID.

I was bored and was looking for new things to read. Finishing my English Literature degree gave me access to a reading list I might not have had otherwise. It also gave me access to an English Literature professor who was happy to chat with me about the course material because no one else attended her virtual office hours.

As my academic advisor commented when I selected my final courses, “Oh, you work at Google, I guess you didn’t need this degree,” she said.

I don’t work at Google anymore.

But I think it is fair to say, I evaded the sheepskin effect, a phenomenon in applied economics that suggests that people with a completed academic degree earn higher income than those with an equivalent amount of study without an academic degree.

Gabriel will evade it, too.

Not every 4th grader will be so lucky.

In addition to any academic skills or knowledge I may have retained, my university experience taught me a lot of other things.

I learned how to negotiate with my professors for extensions on essay due dates.

I learned how to fix a broken electric stapler at the computer lab where I worked.

I learned how to build websites.

I learned that dating a PhD student (who was studying in your academic program) gave you a massive advantage (over your peers) when having your essays edited by that PhD student.

I learned about Mexican food (we didn’t eat much Mexican in Wiarton in the 1980s and 1990s).

I learned how much beer was too much beer to drink in a single pub night.

And I’m not sure that ChatGPT is going to teach you all of those things.

But I also know that professors and instructors at colleges and universities need to have a real, honest conversation about how they can use AI in their lectures and seminars to teach kids how to be ready for a future neither Funk nor Wagnalls could have predicted.

“AI will force us humans to double down on those talents and skills that only humans possess.”

– David Brooks, New York Times

AI that works like a teammate, not a chatbot

Most “AI tools” talk... a lot. Lindy actually does the work.

It builds AI agents that handle sales, marketing, support, and more.

Describe what you need, and Lindy builds it:

“Qualify sales leads”

“Summarize customer calls”

“Draft weekly reports”

The result: agents that do the busywork while your team focuses on growth.